Over 16 years ago I moved from Dublin city to the wilds of the Beara Peninsula, West Cork. Ever since, the seasons have taken on incomparably more meaning in my life. Every passing year is now measured by cyclical change in the temperate rainforest and other natural habitats on the 73-acre farm I live with, and each period has its own very special charms.

The autumn fall of forest leaves, nourishing the woodland floor with new organic matter for all nature’s biodigesters to turn into rich soil and food for new life. A wild eruption of fungi, in all sizes, shapes, and colors: many the fruiting bodies of complex underground mycorrhizal matrices that link the trees together: nature’s combined telegraph wires and aid distribution network.

Winter dormancy, a time of skeletal oaks revealing their true gnarled, twisting, sculptural forms; of low, thin sunlight raking the sleeping ecosystem. This is the best moment to seek out and remove alien invasive plant species like rhododendron from the forest, their evergreen glossy leaves much more evident when native vegetation has temporarily died back.

In spring, carpets of wildflowers bloom in the rainforest: celandine (almost always the first), wood sorrel, dog violet, primrose, pignut, bluebell, yellow pimpernel, wood anemone, enchanter’s nightshade, cow-wheat, kidney saxifrage, marsh violet, to name but a few. Up in the canopy, leaf buds begin to burst open, each one a photosynthetic solar panel, transforming atmospheric carbon pollution into rich life.

Growth reaches its maximum through the summer months, the plant community working hard to power the entire ecosystem. Another layer of woody tissue is laid down around tree trunks, building on the concentric rings of previous years, each successive width dependent on the productivity permitted by warmth and rain levels. And for me, over the last few years, late spring to early summer is also the time when I’m busy with my Opinel number 12 pocketknife, if a free hour or two presents itself. I’d better quickly explain before anyone gets the wrong idea.

Throughout the years in Beara, I’ve been engaged in restoring what was a dying forest and creating the conditions for it to expand in area. The problems were multiple, but at the core was ecological meltdown due to acute overgrazing. Sheep, plus invasive feral goats and sika deer, had been preventing the trees and other flora from regenerating by eating away virtually all native vegetation at ground level.

Fencing the invasive grazers out gave rise to the most miraculous metamorphosis across most of the land, as native trees began to seed out profusely, and ground that had been shorn of life began to revert to its hugely diverse, natural state of temperate rainforest.

But in some areas amounting to several acres, lifting the grazing pressure wasn’t enough. Bracken, a native fern largely inedible to mammals, had taken over and, where especially dense, was smothering trees and everything else. Monocultures of this plant are now widespread across Ireland and should be considered completely artificial: they arise because overgrazing causes forests to die off and be replaced by the only thing no animal eats.

Interestingly though, in my own place I noticed that, where I cut access paths through the bracken, wild self-seeded trees quickly took advantage and corridors of saplings began to spring up: birch, willow, rowan, oak, hazel, hawthorn, and others. That got me thinking.

In the spring, I’d often spot tree seedlings here and there, but these would be swamped when a new sea of bracken emerged some weeks later, and so become impossible to find. So I began marking the location of baby trees I came across by hammering in a wooden fencing stake alongside, and periodically returning to lop the heads off the ferns as they came up, roughly between late April and early July. Bracken is very tender at this stage, so a sharp blade slices through stems effortlessly; in contrast, it’s much tougher when mature.

The assistance I give is necessary solely in the immediate vicinity of a small tree, allowing it to reach the light. And it’s temporary: once trees grow beyond the chest-high bracken tops, they’re able to carry on by themselves and will ultimately shade the fern out, returning it to its natural niche as just another component of the ecosystem. Nor do I feel the need to cut around every last tree: those that germinate further from others are prioritized. Slower growing species like oak also get a bit more love, since the pioneers (birch, willow, and rowan) are much better able to exploit any break in bracken cover and rocket up through.

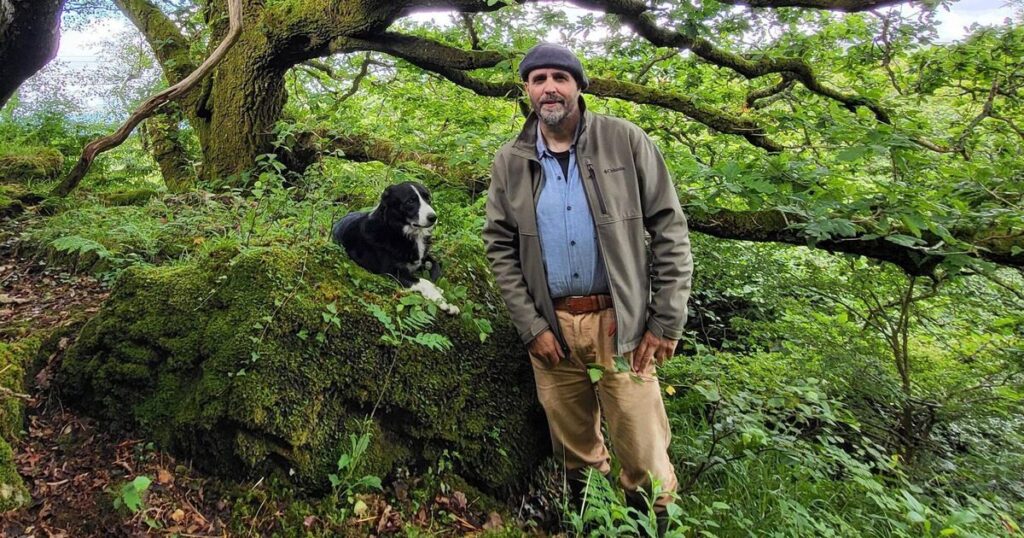

My son’s collie dog, Charlie, accompanies me on these forays, playing his role as ‘wolf’. Again, some explanation is required. This particular area was never deer-fenced, so sika occasionally pass through and nibble on regenerating saplings. My theory is that Charlie’s scent, which I like to imagine instinctively equals predator in a deer’s mind, discourages them from hanging around. Despite occasionally finding a few odd droppings or signs of browsing, this approach seems to generally work, and I recently read an academic paper suggesting there’s more to this than just wishful thinking on my part.

Although at an early stage, the results of this new approach have been just wonderful, with most of the bracken-infested area now reverting to natural, native forest. And, just like the mature habitat elsewhere on the land, the natural regeneration will make for so much better, richer habitat than any planted trees. Here, they grow only where nature, not man, decreed: perhaps from a crack between large bounders, or from the side of a rockface, or two different species wrapping around each other as they develop. The diversity of outcomes is practically endless, in stark contrast to the monotonous uniformity of planting.

Further, despite its drawbacks, the bracken creates the right conditions for a specialist forest flora to persist – low light and high humidity levels through much of the spring and summer. When the land was grazed by sheep, these wildflowers would have been barely evident, and just about hanging on. They’ve now been released and form great carpets of color before the bracken comes up, in stark contrast to the other side of the sheep fence, which has stayed barren.

The presence of this plant life is a massive bonus. As a general rule, natural regeneration of trees can often be extremely fast, but the associated biodiversity far slower to follow, especially if not connected to old woodland. In my place on the other hand, a rich ground flora has been here since the area was last forested, probably several centuries ago, waiting for the trees to return.

Some people might consider what I’m doing with the bracken ‘highly labor-intensive’, but it’s really not. It doesn’t take long to make my rounds, and I easily manage to fit it in with the rest of my often-busy routine. I’m currently working on a third book (on rewilding in Ireland, again due to be published by Hachette), so spending some time engaged in non-taxing physical activity is the perfect antidote to sitting in front of a computer screen.

To tell the truth, I yearn for those moments when I can get away and spend an hour or two at this ‘work’. It’s a deeply therapeutic time out, my mind dreamily observing what’s going on in a self-creating ecosystem, surrounded by birdsong, fluttering butterflies, buzzing wild bees, perhaps the sun and a gentle breeze on my face. It’s no exaggeration to call it a meditation, time and space for contemplative mind wanderings, as I physically wander through a wondrous wilderness that only a few years before didn’t exist.

Working together with nature to heal man-inflicted wounds is one of the most positive things we can do. And that knowledge is there, at the back of my mind, throughout. When the land has, in the future, fully reverted to natural forest, habitat for thousands of different species of animals, plants, and fungi, there’ll be an immense satisfaction in remembering the bracken monoculture that I first found there.

But there’ll also be some regret: that I can’t spend an occasional couple of summer hours with my trusty Opinel, helping birth a wild rainforest ecosystem.

- Eoghan Daltun has documented his rewilding work near Eyeries on the Beara peninsula in two books: and